Was Senator Scott Surovell’s recent article in the Richmond Times Dispatch, “Helene sends a message: Virginia must rejoin RGGI,” an honest misunderstanding about hurricanes and about how the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) works (or doesn’t work) or was it a blatant use of a serious weather tragedy to score political points against a popular Governor — all while communities were still suffering and rescue efforts were still underway? In either case, Virginia deserves better from the Senate Democrat Majority Leader.

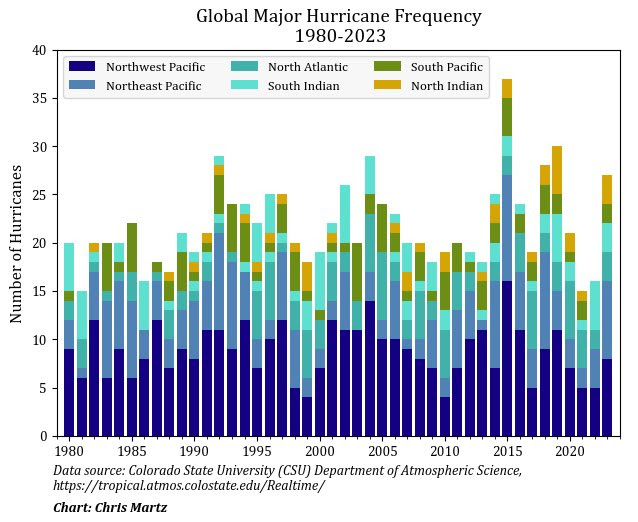

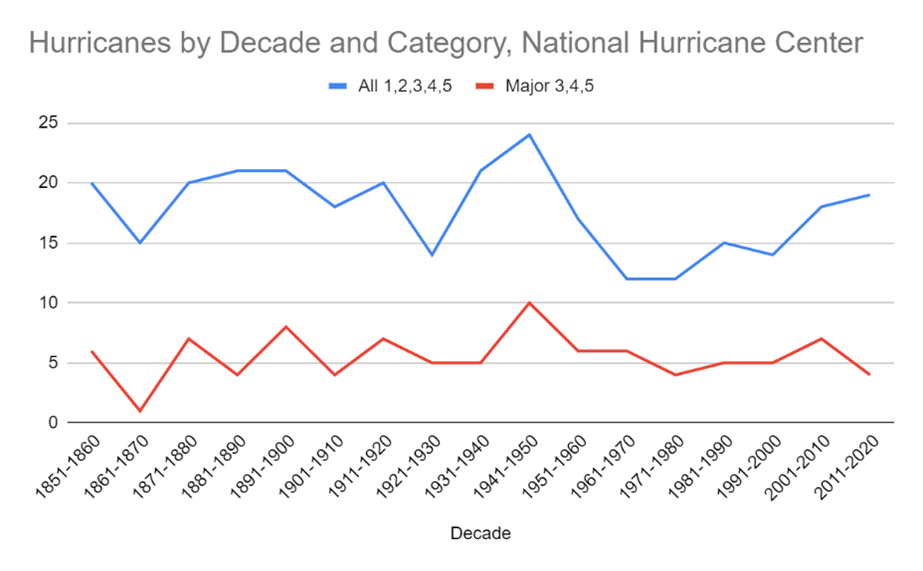

Here are the facts. First, there is no evidence that hurricanes have increased in number or intensity. The National Hurricane Center chart below shows the number of major hurricanes since 1851 and breaks out category 3,4, and 5 hurricanes to measure intense hurricanes over time. As you can see there does not appear to be an upward trend in overall hurricanes or in high intensity hurricanes. Recency bias cannot even explain the climate hysteria evident in current hurricane reporting.

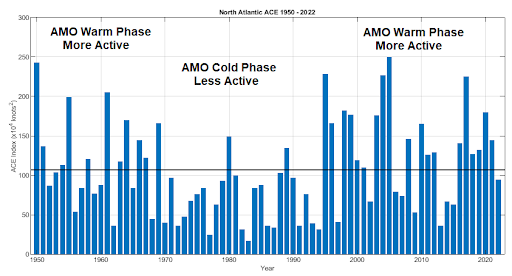

Second, there is strong evidence that the wide fluctuation in hurricanes and intensity over time is not related to global warming, but to an ocean surface temperature pattern known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). If you overlap AMO patterns with hurricane activity, you can see that the variation in hurricane numbers closely align with this naturally occurring surface temperature pattern. You will also see that we are in a more active phase due to the current state of the AMO.

Setting aside the fact that there is little evidence that hurricanes have gotten worse, or that man-made carbon emissions have had any impact on the number or intensity of hurricanes, the more important point is that membership in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) has not reduced carbon emissions. In fact, according to a recent report by Thomas Jefferson Institute’s Steve Haner, in the first two years of RGGI membership, CO2 emissions actually grew by 3.7 million tons. Virginia’s membership in RGGI is having the exact opposite effect than was expected.

As per Senator Surovell’s argument that the use of the $800 million in revenue collected under RGGI’s significant tax structure over the last three years could have mitigated this flooding, he clearly misunderstands how this money was spent. Fifty percent of RGGI funds were used for energy efficiency spending on low-income homes. Does anyone believe that Energy Efficient (EE compliant) refrigerators or greater insulation in the homes of lower income families would have mitigated the impact of Hurricane Helene? Of course not.

In fact, our own study showed that the Energy Efficiency program as approved by the General Assembly and run by Dominion Energy Virginia, increases energy use by either replacing zero carbon producing broken appliances with carbon using working appliances, or families keeping their older appliances as a “backup” while taking advantage of the EE program to buy a second more efficient appliance. Think of moving your old refrigerator into a basement or garage, after you replace it with the government subsidized EE refrigerator.

Another 45 percent of RGGI funds were used for “flood preparedness,” which may be where Senator Surovell got confused. But this was not the kind of “preparedness” that would have prevented the massive flooding we saw from hurricane Helene. Setting aside that a lot of this funding was used for “planning and education” — the actual flood prevention and protection projects were spent on creating “Living Shorelines” by using natural elements like vegetation and oyster reefs to stabilize shorelines and reduce erosion, providing a more sustainable and resilient alternative to traditional hardened structures like seawalls. The City of Hampton received funding for living shoreline projects along the Chesapeake Bay. Would any of this prevent damage from a category 3 hurricane? Of course not. Hardened structures may have been a better alternative.

Other RGGI funded projects included “Tidal Marsh Restoration” to restore degraded tidal marshes to help absorb floodwaters and protect coastal communities from storm surges as was done in the Town of Chincoteague on the Eastern Shore. There was also “Stormwater Management Infrastructure” spending used to upgrade stormwater systems to handle increased rainfall and reduce flooding in urban areas. The City of Norfolk, for instance, received funding to improve its stormwater infrastructure, as did both Fairfax and Alexandria. Again, such systems are important, and surely useful to prevent damage from more casual storms or minor increases in sea levels but are meaningless in the face of a category 3 hurricane.

There was a small amount of funding for “Inland Communities” like the ones that did suffer damage from hurricane Helene here in Southwest Virginia. Some of this funding went to improve drainage systems and constructing barriers in high-risk areas. But again, all such efforts were overrun by the massive amount of rain from this high intensity hurricane.

The remaining 5% ($40 million) of RGGI revenue was spent on the administrative costs of implementing and managing this program. These are administrative costs separate from the planning and educational spending mentioned earlier. Again, a large expenditure with no real added benefit and of no use against hurricanes, obviously.

Senator Surovell should know that weather disasters are a sad fact of life. In 1957 President Eisenhower declared 28 Appalachian counties disaster areas due to the massive flooding in Southwest Virginia, Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. A flood in 1870 started in Charlottesville and destroyed entire towns and farms throughout the Shenandoah Valley. In 1969 Hurricane Camille hit Virginia and caused inland flooding and mudslides that killed over 150 people. The list of floods and devastation is long and troubling but are acts of God unrelated to carbon emissions and government programs. Their occurrences are random and happened before and after the age of man-made carbon emissions.

Senator Surovell surely knows that Virginia doesn’t need to be in RGGI to fund flood mitigation projects. Instead of playing politics over the disastrous Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, he should be sitting down with the Governor and local leaders to see what could have been done, if anything, to prevent damage from this or other hurricanes or other weather events. That is the Virginia way.