There’s no better way to introduce you to the breakthrough ideas that creative-class guru Richard Florida has explored in his latest work, “Who’s Your City?” than to show you a map that appears midway through the book.

By way of preface, Florida has drawn upon a school of social psychology that has identified five fundamental personality traits by which all individuals vary: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion (sociability), agreeableness and neuroticism. For each of these traits, an individual can be plotted along a spectrum between two poles — between introverted and extroverted for instance, or between calm and high-strung.

Psychologists have mapped the geographic location of some 600,000 Internet survey respondents, showing clearly that different personality types vary in frequency by region. That finding piqued the curiosity of Florida, who popularized the idea in his earlier booked, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” that the artistically, scientifically and economically creative members of society are migrating to a centers of innovation that produce an increasingly outsized share of the nation’s wealth.

In his new book, Florida poses queries that few economic developers would ever think to ask. Could cities and regions take on personalities of their own, which over time attract certain kinds of like-minded people? If so, what are the implications for regional economic development?

One of the five personality maps in “Who’s Your City” shows that people with “neurotic” personality traits — i.e. those who are nervous, high-strung, insecure and prone to worry — are highly concentrated in the Northeastern U.S., particularly around New York City. Secondary clusters reside in the “rust belt” sector of the Midwest, and in Kansas-Oklahoma.

This map plots concentrations of nervous/high-strung survey respondents (as contrasted to those who are calm/relaxed).

The distribution of personality types has implications for regional economic development, argues Florida. Kvetching and creativity, it appears, are incompatible. “Neuroticism is negatively associated with top talent in the form of human capital or the supercreative class,” he writes.

Conversely, he adds, “Regions with high concentrations of highly educated and ultra-creative individuals tend to be more emotionally stable, less volatile and more resilient. This suggests, among other things, that these are places where people may be more likely to take risks because they’re less concerned about failure.”

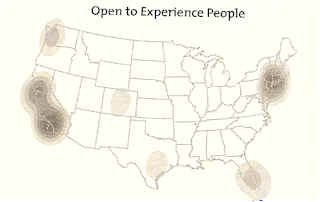

The personality trait most closely aligned with creativity, Florida suggests, is an openness to new experiences. That trait is found most heavily in the Northeast and the West Coast, with pockets in Colorado, Texas and southern Florida. “Openness to experience is the only personality type that plays a consistent role in regional economic development,” he writes. “It is highly correlated with jobs in computing, sciences, arts, design, and entertainment; with overall human capital levels, high-tech industry, income and housing values.”

This map plots concentrations of survey respondents who

are open to new experiences (as contrasted to those

who are close-minded).

(Fortunately for the economy of Gotham, New York City is a focal point of “open to experience” personalities as well as neurotics.)

By exploring the intersection of psychology and economic development, Florida has advanced his theories about the creative class far beyond the thinking that inspired “The Rise of the Creative Class.” Postulating that the percentage of creative-class occupations in a region was closely correlated with metrics of innovation and wealth creation, he argued then that the creatives were migrating to regions noted for the authenticity of urban experience, openness to newcomers, tolerance for cultural and ethnic diversity, and general coolness. His theories sparked a wave of municipal and regional initiatives to make themselves attractive to these wealth creators.

In “Who’s Your City,” Florida delves deeper into the sorting process that he sees at the heart of the great migration taking place in the United States. He now offers two more refined explanations for the forces driving the migration. One is economic, the other psychological.

In 1970, Florida notes, human capital was distributed fairly evenly across the country. Over the past three decades, the percentage of Americans with college degrees has doubled, but the gains have gone overwhelmingly to regions like Washington, D.C., and San Francisco while largely bypassing regions like Detroit and Cleveland.

What’s driving the migration? Florida argues that the most talented and ambitious people need to live in the anointed regions in order to maximize their full economic potential. And in a virtuous cycle, the influx of talented and ambitious people spurs the productivity and innovation at the heart of wealth creation. The superstar cities surge ahead economically and cities like Motown figuratively spin their wheels.

But there’s another process at work, Florida suggests. Not all Americans are driven by a desire to maximize income. For many, the decision of where to live is as important to the pursuit of happiness as the choice of a spouse. Americans seek communities that best “fit” their personalities.

Geographic differences in personality, Florida says, could have emerged as a result of immigrants selectively migrating to places that met their psychological needs. Among the five major personality types, people who display high levels of openness to experience are both the more adventuresome and the most mobile. They are the ones most likely to pick up from Dullsville and move somewhere more exciting.

Florida then takes his thinking one step further: “Perhaps the same types of people who are the most likely to move are also the ones most likely to innovate and start new firms. As more and more of the people leave the places where they were born and cluster together, the concentrations become hotbeds of creative endeavor, innovation, start-up companies, and economic growth.”

I find both the economic and psychological explanations to be persuasive. Both work in tandem to herd the restless, novelty-seeking and wealth-creating elements of society into a relatively small number of regional crucibles of creativity. Curiosity, energy, intensity, novelty seeking, exploration — all these attributes do tend to go together. In a different stage of history, such traits might have gotten people burned as heretics, shunned as eccentrics, or banished to the colonies. But in an age of unprecedented scientific discovery, economic dynamism and cultural change, such qualities become great virtues. In the 21st century, such traits make people millionaires.

Where does all this leave Virginia? Well, the Old Dominion is situated at the edge of a major culture cluster found mainly in the Southeastern U.S. and the Midwestern states. Most of Virginia is dominated by two personality traits: agreeableness and conscientiousness.

These qualities sound positive, and to some extent they are. “Agreeable types are warm, friendly, compassionate and concerned for the welfare of others,” Florida writes. “They generally trust other people and expect other people to trust them.” Agreeable people are nice to be around. They build communities of trust. Regions full of agreeable people tend to be more pleasant places to live. Which is great, if “pleasant” is what you’re looking for.

On a more positive note, agreeable people work together in teams and collaborative environments better than disagreeable people do, and Florida’s massaging of the data suggests that there is a slight correlation between agreeableness and a regional capacity to innovate. Thus, from an economic development perspective, this trait is a mildly positive attribute.

This map plots concentrations of agreeable survey

respondents (as contrasted to those who are disagreeable).

Virginia also falls into the personality zone strongly associated with conscientious people. “Conscientious types work hard and have a great deal of self discipline. They are responsible, detail-oriented, and strive for achievement,” Florida states. They tend to be better-than-average workers on almost any job.

While it’s important to have conscientious people on any team, says Florida, conscientiousness as a dominant personality type does not stimulate regional innovation. “Conscientious individuals tend to be rule-followers,” he says. Give them a clearly defined task and they will develop the most efficient procedure for completing it. But when the task is not clearly defined and requires creative thought, conscientious individuals may struggle.

This map plots concentrations of conscientious survey

respondents (as contrasted to those who are disorganized).

The maps for agreeable and conscientious personality types show significant overlap — they are the defining characteristics of the Southeastern U.S. Florida refers to this overlapping cluster as “conventional or dutiful.” Dutiful regions are a good fit for model citizens, who want to fit in, who hold conventional or traditional values, who obey the rules and don’t step out of line. People tend to trust one another, and tend not to challenge authority.

That’s a recipe for a more stable, harmonious society. But watch out, Florida warns: “The status quo orientation and don’t-rock-the-boat values of those regions might not only damp down creativity and innovation … but also encourage an outmigration of the open types who tend to be the source of new creative energy and innovation.”

Wow. Such concerns take economic development a long way from industrial parks and Interstate highways. Deconstructing a region’s psychological profile makes the job a whole lot harder. As Florida observes, it’s one thing to attract a company or build a new stadium; it’s quite another to alter the psychological make-up of a region to make it attractive to the creative, open-to-new- experiences types who propel the economy. Frankly, most regional leaders wouldn’t have the slightest idea of where to begin to make the needed changes — or even if they wanted to.

But deciphering the dynamics of why people in our mobile society move from one region to another is a challenge that every region needs to grapple with. If human capital is the driver of economic development in the 21st century, as it assuredly is, regional leaders must understand why the most economically innovative and productive people choose to live in a relatively select number of places. “Who’s Your City?” is hardly the last word on the subject. But Richard Florida has identified some of the key issues and given us a framework for thinking about them.

— June 2, 2008

Post script. The fifth basic personality characteristic is extroversion: the degree which people are extroverted or introverted. On the whole, Southerners are extroverts — but the boundaries cut through central Virginia. The population centers in the eastern part of the state do not markedly display this trait. Florida did not identify any strong correlations between this characteristic and economic performance.

This map plots concentrations of extroverted survey

respondents (as contrasted to those who are introverted).

Note on maps: Large swaths of the country in these maps appear blank. Do not take that as a sign that the people living there have no personality at all! Although Florida provides no explanation, I would surmise that the blank spots reflect the fact that an insufficient number of survey responses were gathered in the corresponding zip codes to reach statistically valid conclusions.

- The Most Progressive Budget in Virginia’s History - December 21, 2019

- When is a Clean Water Act Permit Needed? - December 21, 2019

- Should U.S. Consider Modern Monetary Theory to Improve Economy? - December 21, 2019